date

seminar

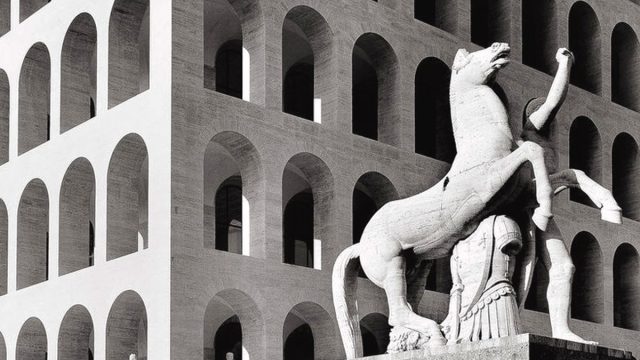

Aristotle Kallis “The banality of fascism”

Little over a hundred years ago the word 'fascism' was meaningless. Only a few 'dense' years later it had graduated into a formidable trope, first in Italy and very soon across an ever-expanding range of countries. Superlatives have accompanied historical accounts of fascism ever since its appearance in crisis-ridden post-WW1 Italy. Surely something as extreme, repressive, murderous, and devastating in the most real sense of the word as 'fascism' cannot be spoken about in any terms other than the language of the unique and the extreme.

Yet, if we shift for a moment the focus from the praxis and the outcomes to the reasons behind fascism’s formidable international traction in the interwar years and its endurance over time, we encounter a different picture. Like a potent alchemy, fascism was forged from the existing base metals of nationalism and deep-rooted fears of the ‘other’, from sedimented prejudices and contemporary anxieties about crises, real or perceived. It also promised the illusion of history-making agency to those who felt disempowered and subjugated by the historical mainstream. Fascism’s ideological and political formula may have been unique, extreme, and brutal but its drivers were (and continue to be) disturbingly commonplace, indeed banal. This explains why, in the midst of a profound crisis of liberalism and of a collective paranoia against the spectre of a socialist revolution, interwar fascism gained traction so quickly among people and elites across countries, regions, cultures, and political spaces.

If fascism may indeed be ‘banal’ in this sense, as I will argue, then the fight against it needs to be refocused on the mainstream fundamentals that drive its ongoing appeal. In the past fascism gained traction and was diffused internationally not because of some mysterious collective lapse into unreason and extremism but through incremental, banal affirmative choices for many. Its power of attraction derived from a deep reservoir of crises, fears, and long-standing prejudices, building on run-of-the-mill motifs about national community and sovereignty, expressing a longing for defending a seemingly threatened identity and for wresting agency that appeared in retreat. All these fundamentals remain as painfully relevant and resonant today as in the past. Therefore fascism’s potential for resurfacing, one way or another, and for gathering fresh (if different) momentum today or in the future remains largely undiminished.

bio

Aristotle Kallis is professor of modern and contemporary history at the School of Humanities, Keele University. He received his BA Hons from the University of Athens, Greece and his PhD from the University of Edinburgh. He has previously taught at the Universities of Edinburgh (2000-2002), Bristol (2002-2003), and Lancaster (2003-2016).

His main research interests lie in the fields of fascism/extremism, on the extremism-mainstream nexus in contemporary politics, and on the history of urban modernism. Ηe is currently working on two projects – one on fascism and iconoclasm and the other on the normalisation and ‘mainstreamining’ of the radical right since 2001.

His most recent publications include The ‘minimum dwelling’: a practical utopia (forthcoming, 2023); Beyond the Fascist Century (co-edited with Constantin Iordachi, 2020); Fascist Rome: The Making of the Fascist Capital (2014) and Rethinking Fascism and Dictatorship (co-edited with Antonio Costa Pinto), as well as a series of articles and chapters on interwar fascism, the radical right, Islamophobia, and the ‘mainstreaming’ of populism.

seminar video

seminar video

date

bio

Aristotle Kallis is professor of modern and contemporary history at the School of Humanities, Keele University. He received his BA Hons from the University of Athens, Greece and his PhD from the University of Edinburgh. He has previously taught at the Universities of Edinburgh (2000-2002), Bristol (2002-2003), and Lancaster (2003-2016).

His main research interests lie in the fields of fascism/extremism, on the extremism-mainstream nexus in contemporary politics, and on the history of urban modernism. Ηe is currently working on two projects – one on fascism and iconoclasm and the other on the normalisation and ‘mainstreamining’ of the radical right since 2001.

His most recent publications include The ‘minimum dwelling’: a practical utopia (forthcoming, 2023); Beyond the Fascist Century (co-edited with Constantin Iordachi, 2020); Fascist Rome: The Making of the Fascist Capital (2014) and Rethinking Fascism and Dictatorship (co-edited with Antonio Costa Pinto), as well as a series of articles and chapters on interwar fascism, the radical right, Islamophobia, and the ‘mainstreaming’ of populism.

seminar video

seminar video

seminar

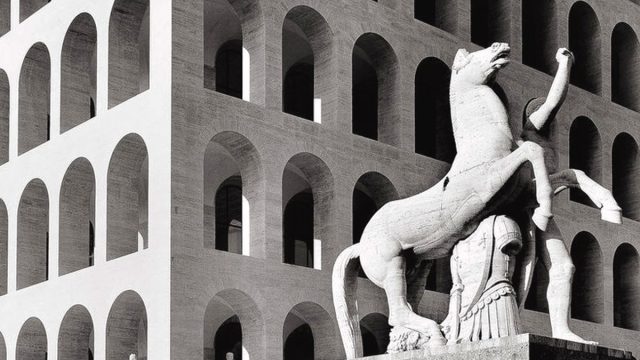

Aristotle Kallis “The banality of fascism”

Little over a hundred years ago the word 'fascism' was meaningless. Only a few 'dense' years later it had graduated into a formidable trope, first in Italy and very soon across an ever-expanding range of countries. Superlatives have accompanied historical accounts of fascism ever since its appearance in crisis-ridden post-WW1 Italy. Surely something as extreme, repressive, murderous, and devastating in the most real sense of the word as 'fascism' cannot be spoken about in any terms other than the language of the unique and the extreme.

Yet, if we shift for a moment the focus from the praxis and the outcomes to the reasons behind fascism’s formidable international traction in the interwar years and its endurance over time, we encounter a different picture. Like a potent alchemy, fascism was forged from the existing base metals of nationalism and deep-rooted fears of the ‘other’, from sedimented prejudices and contemporary anxieties about crises, real or perceived. It also promised the illusion of history-making agency to those who felt disempowered and subjugated by the historical mainstream. Fascism’s ideological and political formula may have been unique, extreme, and brutal but its drivers were (and continue to be) disturbingly commonplace, indeed banal. This explains why, in the midst of a profound crisis of liberalism and of a collective paranoia against the spectre of a socialist revolution, interwar fascism gained traction so quickly among people and elites across countries, regions, cultures, and political spaces.

If fascism may indeed be ‘banal’ in this sense, as I will argue, then the fight against it needs to be refocused on the mainstream fundamentals that drive its ongoing appeal. In the past fascism gained traction and was diffused internationally not because of some mysterious collective lapse into unreason and extremism but through incremental, banal affirmative choices for many. Its power of attraction derived from a deep reservoir of crises, fears, and long-standing prejudices, building on run-of-the-mill motifs about national community and sovereignty, expressing a longing for defending a seemingly threatened identity and for wresting agency that appeared in retreat. All these fundamentals remain as painfully relevant and resonant today as in the past. Therefore fascism’s potential for resurfacing, one way or another, and for gathering fresh (if different) momentum today or in the future remains largely undiminished.